Almost every pinhole photographer I talk to today is using a smart phone app to do their exposure measurement. There’s some holdouts who use the Sunny 16 rule. There’s the occasional pinholer who’s got a trusty Pentax Spotmeter or the latest Sekonic digital meter. But by and large, pinholers today are using smartphone apps, and so am I.

The smartphone apps are an amazing development of convenience – nobody leaves their house without their phone anymore, so it just makes sense. Getting a passable exposure is a no brainer. But we’re not here today to talk “passable” – no, today we’re going to talk about wielding this tool to create the image you’ve pre-visualized. Have you ever taken a shot where you expected a one portion of the scene to be rich in detail and tone, but what you get back from the lab in either unusably dark or completely blown out? Yep, we’re gonna fix that today!

Grab a cup of coffee or tea – this is a lengthy one

Deceptions in Smartphone Apps

The first step is to understand that while your smartphone app is amazing, if you don’t know some details, it’s lying to you. Here’s some of the ways:

- If auto-brightness is turned on, the screen display is almost always going to be brighter than what the reading says

- Without the spot meter enabled, it can be difficult to make decisions on the scene you want

- Your smartphone screen has a different dynamic range than film

- Certain screens have inherent color casts

- Reflections off the screen can mean that problem areas of the scene aren’t noticed

Solution: Return of the Zone System

I grew up before digital, when you had to sweat it out in a darkroom for hours trying to rescue a bad exposure. While film was cheap, time wasn’t, so Ansel Adams’s Zone System was a great shorthand in that day. Lately, a lot of photographers eschew the Zone system referring to it as antiquated – in many situations, they’re right. The light meters these days are better, film and digital latitudes are longer, and if you’re shooting digital, you can “chimp” the histo till you’ve got the exposure.

But of course there’s no light meter in our pinhole cameras. And the apps have the shortcomings noted above. So once again, the Zone System becomes a useful shorthand to ensuring you have the exposure you want.

What I’m going to describe here is what I call a “loose” Zone System. Why “loose”? Because the Zone System should be used with a spot meter, and that “spot meter” on your phone isn’t a true 1º spot meter – the iPhone is more like a 10º spot, maybe even 15º. This means that when you read areas for a Zone, you’re going to be reading more than you might want to be. So Zone System purists I apologize, but everything relies on that bigger swath of metering.

What is the Zone System?

If you’re not familiar with the Zone System, I’m not going to do a full write up here – plenty others have done that job extremely well already. Here’s a very very brief shorthand:

- There’s 10 zones, or distinct exposure levels, in print latitude. Zones correlate to stops in exposure

- Zone 0 is pure black

- Zone III is the lowest shadow value with detail

- Zone V is “middle gray”, what your light meter reads, and what you expose at

- Zone VI is typical caucasian or asian skin, while Zone V is typical African American skin, and darker skin types can be as low as III

- Zone VII is the typical highlight value with detail – but if you know what you’re doing, you can get detail in IX or X

- Zone X is pure white

Want to learn more? The rabbit hole is deep – here’s a good primer: Norman Koren Simplified Zone System

Applying the Zone System with a Smartphone App

As I alluded above, typically the Zone System calls for a 1º spot, but a smartphone has a 10º or 15º spot. Traditionally you use the 1º spot meter so that when you read a portion of your scene, you’re just getting that Zone of exposure. Since smartphone apps have such a large “spot”, we need to slightly adjust how we use the Zone System to get the exposure we want.

So here’s my process to get loose on this concept and still get the details I want:

- Determine the composition of the scene

- Open my smartphone app and turn on the spot meter setting

- Meter every area of the scene that you want detail in, writing down the EV values

- Mark the lowest EV value you read as Zone III

- Add 2 to the EV value in step 4 and that is my Zone V

- Add 4 to the EV value in step 4 and that is my Zone VII

Now that you have your scene “mapped” by zones, you can evaluate the exposure. If based on the above you have the shadow and highlight details you want, and your mid ranges are right, then you can expose for the reading at Zone V. However if your shadows will be too light or your detailed highlight above Zone VII, you might want to reduce the Zone V exposure by one or more stops before shooting that reading. Alternatively, if your shadows are too dark or highlights will be on Zone V, you may want to expose your Zone V reading longer. Remember when making these adjustments: 1 zone = 1 stop of exposure!

Zone system purists would tell you to get your smartphone closer to try and get more detailed reading on the shadow and highlight detail areas. For lens based photography I would agree, however for pinhole I feel that the larger sensing area of the smartphone app “spot” is appropriate due to the reduced detail available in pinhole photos.

Real World Example 1

If this your first foray into Zone System photography, the above was probably confusing to you. The following example may shed some needed light on the process.

Near my office I wanted to take a photo of some old smoke stacks. I’ve photographed them before, but they’ve always come out boring. Today was a windy day, so I thought I’d take a stab at using the wind-whipped branches blurred in the foreground to add some drama. I’ll know in a few weeks if it worked. In the meantime…

I approached the scene knowing my framing and wanting to see the range of values. I got the lowest value in the base area of the tree. I got mid values in the upper area of the tree. I got high values in the sunny mid-day sky. Here’s my readings:

[bscolumns class=”one_third”][singlepic id=441 w=200][/bscolumns][bscolumns class=”one_third”][singlepic id=442 w=200][/bscolumns][bscolumns class=”one_third_last”][singlepic id=443 w=200][/bscolumns][bscolumns class=”clear”][/bscolumns]

Note that these readings line up almost perfectly to my process:

- Zone III: EV 13

- Zone V: EV 15 1/3

- Zone VII: EV 17 1/3

Also note that if I weren’t using Zones and just relying on the full screen or even on a single reading:

- The sky would have been blown out in the EV 13 example

- The smoke stacks and foliage would have been darker than I wanted in the EV 17 1/3 example

Ultimately I made a 1 second exposure for the photo. Since everything was going to be in motion, I was OK with losing a smidge of shadow detail, but I could gain some better cloud streaks.

Real World Example 2

I know you’re thinking that that example was just too damn convenient, because of the way the zones lined up just right. Honestly, they often do in outdoor scenes, but in this example let’s look at how zones help us when things aren’t just right.

In this indoor scene, I want to capture some details of the radiator and wall inside the stairwell as well as some of the clouds streaking by outside. When I look at the scene through my phone, it looks like it should be possible, but lets see how some of the reading stack up:

[bscolumns class=”one_fourth”][singlepic id=444 w=150][/bscolumns][bscolumns class=”one_fourth”][singlepic id=445 w=150][/bscolumns][bscolumns class=”one_fourth”][singlepic id=446 w=150][/bscolumns][bscolumns class=”one_fourth_last”][singlepic id=447 w=150][/bscolumns][bscolumns class=”clear”][/bscolumns]

If I map this the way I did in example 1, then I’d get:

- Zone III: EV 7 1/3

- Zone V: EV 10 1/3

- Zone VII: EV 12

- Zone X: EV 15 1/3

Hmm… that might not quite be the exposure I was hoping for, because I do want the clouds to streak by some, but putting the upper window are on Zone X would probably blow them out. Then again, if I put the upper window on Zone VII, that will knock the radiator down to Zone 0. A creative decision needs to be made here – the important thing to take away is that without understanding how to map these readings to Zones, my creative decision would just be a guess.

Closing Notes

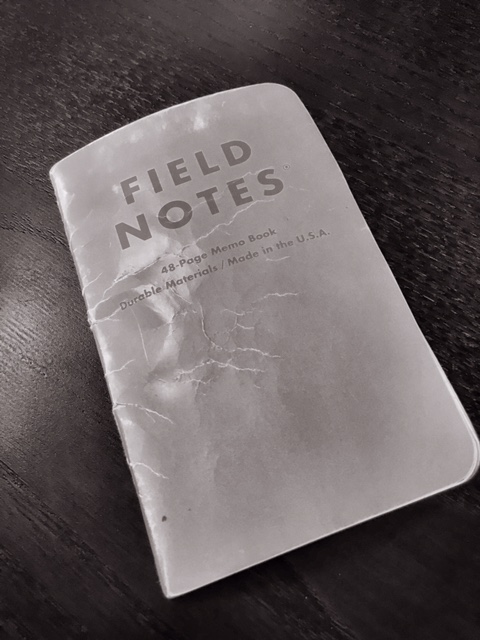

I hope this walkthrough helps your creative journey. Once you understand how to apply the zones to your pinhole photography, you’ll be able to get more full rolls of “winners” and reduce your reliance on luck. My single biggest piece of advice is this: Take detailed notes! Even if you don’t use the Zone System to drive your exposure decisions, a few notes about different EV readings in the scene will help you review later what went right or wrong with the exposure decision. I keep a notebook in my back pocket constantly just for this purpose.

[singlepic id=448 w=300 float=center]My exposure notebook,

rides in my back pocket every damn day[/singlepic]

[spacer height=”20px”]

A very good article.

The Zone System is surely the most precise way, if you take care with development as well.As a more lazy person i often measure the “incoming” light with an old handheld meter.Works fine most of the time.But understanding the Zone System helps in every way.