Here at ƒ/D, we’re all pinhole, all the time. Looking back at our posts, we’ve recognized that everything we say expects a certain level of understanding. So in an effort to help along those who are just getting interested in pinhole, we wanted to take a moment to address some of those burning questions that might seem like big obstacles to getting started. Have additional questions? Ask them in the comments. Or if you have a hurdle to pinholing that you overcame and would like to share – add those to the comments as well! It’s all about helping the next “generation” (whatever age they may be) of pinholers.

So here we go: 20 Beginner’s Questions About Pinhole

1. How does pinhole work?

Pinhole photography takes advantage of the fact that all light travels in a straight line. There’s a teeny tiny pinhole that only allows a projection of one very small beam of light from the scene you are photographing to hit the film or sensor plane. So with pinhole, you’re using all those beams of light to comprise the image.

2. Does it have to be film?

Nope – it can be film, photographic paper, a digital camera (a DSLR with a pinhole body cap), Polaroid (or instant) film, or alternative photography sensitized materials (such as cyanotype or wet plate). The pinhole just needs to project on something light sensitive for the capture of the image. However, film or paper are the easiest ways to start your pinhole adventure.

[bscolumns class=”one_third”][singlepic id=228 w=150]Mickey on the Merry Go Round, ©Kier Selinsky (Polaroid)[/singlepic][/bscolumns][bscolumns class=”one_third”][singlepic id=314 w=200]Still From a Dream, ©Steven Dempsey (DSLR)[/singlepic][/bscolumns][bscolumns class=”one_third_last”][singlepic id=121 w=200]Under the Trees, ©Marko Umicevic (Paper Negative)[/singlepic][/bscolumns][bscolumns class=”clear”][/bscolumns]

3. What kind of film can be used?

Any kind – 35mm, 120, 220, large format, black and white or color or even IR – so long as it works with your camera, it’ll work for pinhole.

4. Where do I buy film?

Lots of places online such as Amazon (usually more expensive), B&H, and Freestyle Photographic. Film is still widely used!

5. What is reciprocity failure and does it apply to pinhole?

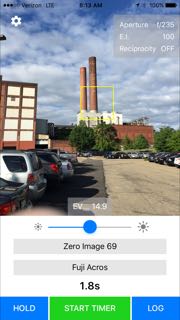

It’s easiest to explain reciprocity failure in relation to normal film performance. Normally, when exposing films, the exposure progresses in a linear fashion, meaning that as you double the exposure time, you double the exposure (brightness) of the image on the film. It’s a reciprocal relationship. Reciprocity failure is when that reciprocal relationship breaks down and doubling the exposure time no longer doubles the exposure. When this happens, you have a correction factor to apply to get the desired exposure level. Reciprocity failure definitely comes into play when shooting pinhole because of the longer exposure times. Don’t worry! There are very cheap tools to help deal with this – see the question on figuring out exposure below. Note: reciprocity failure is why many pinhole photographers use Fuji Acros 100 – it has no reciprocity failure up until 2 minutes of exposure, covering a great many exposure situations without failure compensation.

6. Do I have to have a darkroom?

Nope! Most of us don’t. If you do have one, great! You have more options. Otherwise, this brings us to the next question…

7. Where can I get my film or paper developed and scanned? Is this like a disposable camera?

Film can be developed at home or sent to a lab. It’s worth doing a little Google to see if there’s a film lab in your area – it’s not as uncommon as you might think. If you go local, try to find a pro photo lab, not a drug store, as pro labs will have better scanning services. Another option is mail order labs, such as Richard Photo Lab, Little Film Lab, Indie Film Lab, The Darkroom, and North Coast Photo. If you don’t have a film scanner, have the lab scan your film at the time of development for the most cost effective turnaround. I also recommend getting the highest resolution scan for the whole roll right off the bat. Scanning the whole roll at the highest resolution at development time will usually save you money and time over sending the film back later for a rescan at a higher resolution.

Paper will need to be developed in a dark room. Note that I didn’t say a darkroom – rather, a dark room. It can be a real darkroom if you have access to one. What I do is set up trays in my bathtub, and hang light tight cloth over the door and window, put in a safelight, and I’m ready to process my paper negatives.

In the end though, this is not like a disposable camera where you send the whole thing in to a lab. Whatever film format you use, if you use film, you’ll only be getting the film processed.

8. What gear is required?

A camera and the film or other light sensitive material to go in it. That’s all that’s really required. Also, “camera” in this case can literally just be a shoebox with a pinhole – it doesn’t need to be fancy. Some prefer that it’s not!

9. Do I have to use a tripod?

Only if you want the camera to be steadied and above the ground and other platforms. Otherwise you can handhold it for a cool shaky effect or just set it on the ground or other surface.

10. Do I have to build a camera? How dark does the box need to be?

You don’t have to build a camera – they can be purchased as well. Some of our fave vendors for built cameras are Zero Image, Ondu, NOPO, and RealitySoSubtle. This list is not exhaustive, and there are plenty of boutique makers as well as some “big boys” – the point is, you have options. You could even just buy a pinhole body cap for your DSLR – certainly the cheapest DSLR “lens” you’ll ever buy! If you do build one, it needs to be absolutely light tight to avoid light leaks streaking your film or paper. Do you have access to a 3D Printer? You could just print a camera!

11. Are there lenses for pinhole photography? What if I want to zoom in?

There are 3 ways you can zoom in pinhole:

- Build a camera with bellows (or use a large format camera with bellows). Be sure to change the pinhole diameter for different focal lengths.

- Build or buy a system like the Zero Image 4×5 with multiple focal length frames that can be applied

- Use the “foot zoom” – as in use your feet to walk closer 🙂

12. Can I pinhole without a pinhole camera?

Actually you can! By creating a whole room “pinhole camera”, you can project the outside world in a relatively light tight room, and capture the image with a DSLR. Here’s some Google Image search results to inspire what’s possible.

13. How do you figure out the exposure?

When you get a camera, you’re provided with the ƒ number. Alternatively if you build a camera, you can use a pinhole calculator to find out your ƒ number. The ƒ number is your aperture, and for pinhole they’re typically in the ƒ/100 to ƒ/300 range. Once you have that ƒ number, theres a few ways to calculate exposure:

- Easiest: use a smartphone app

- Printed: make a conversion chart so that you can meter a scene with your regular camera and convert the exposure time from that to your pinhole camera’s needs

- Sunny 16: for the minimalist route, use the “sunny 16” rule and a printed conversion chart to figure your exposures. By learning through experimentation and leveraging film latitude, you can achieve very useable exposures. PhotographyTalk.com has a great write up on how to use the technique.

14. How difficult is it to get an acceptable image?

It’s deceivingly easy. The hard(er) part is learning the unique properties of pinhole and wielding them effectively to make remarkable images. That being said, plenty of photographers get some real zingers from their first roll.

15. Why are some pinhole photos very unusable and blurry, while others are quite sharp?

There’s a few factors involved here. The first is the quality of the pinhole itself. Many people make their own pinholes using a pin to drill through a piece of an aluminum can. While many people are successful with this, the less round that hole is, the more it will distort the image; instead of perfect circles of light making the image, it will be some other shape. Other pinholers (myself included) buy laser drilled or chemically etched pinholes because they are perfectly round. Another factor is how steady the camera was during the exposure – some people have sturdy tripods, while others handhold the camera to create blur and shake. Finally, the pinhole being used might not be the ideal size for the focal length – if it’s too big, the images will be very “soft” and can be perceived as blurry. But again, some people like that and use it very effectively.

16. What types of subjects work well for pinhole?

That depends on your imagination. Anything can be shot well with pinhole, it’s about utilizing the properties of the camera and the long exposure to create the effect you want. Our featured artists give some great examples of the medium’s capabilities. It’s easiest to start with scenes that mix subjects in motion with other elements that stay still (moving clouds over a landscape is a great learning tool). Another great starter recipe is utilizing a super wide angle pinhole camera on super close ups (think inches away) for new and interesting perspectives.

17. Why are some people so focused on pinhole photography?

I can’t speak for all, but I can paint some broad strokes. Some photographers focus only on pinhole because the aesthetic matches their vision. Others like it because the very limited complexity and controls can be liberating in today’s pixel perfect DSLR world. Personally, I enjoy pinhole because it helps me see differently, and the long exposures help me be more mindful of the shot I’m taking.

18. How do some pinhole photos get such extreme wide angles?

Since pinhole has near infinite depth of field, this means that you can get the film plane very close to the pinhole. The closer it is, the wider that angle will be. Since we’re freed from the constraints of having to figure out the complex math in lens creation, you can just try building a camera with a super short focal length and see what you get! Scott Speck is a master of super wide angle.

19. How do some pinhole photos seem warped?

Some pinhole cameras, such as the Pinhole Blender, wrap the film around a curved object inside the camera. Other folks will use paper negatives and crumple the paper in a bowl shape and stuff that into the camera. Some camera, particularly super wide format like 6×12, will have a concave curve to the film plane to try and reduce warp while other 6×12’s will have a flat film plane to accentuate the edge distortion. The near infinite depth of field of pinhole allows camera makers and pinholers to experiment with film plane shapes and angles to come up with some very cool combinations.

20. Why do people disappear in some longer exposures?

Let’s imagine a photo that requires 6 or 7 minutes for the exposure. The scene is filled with people. Remember that when you metered the scene at 6 or 7 minutes, that was what was required to register the objects in that scene at a normal tone (middle gray or middle color value). If a person stays still for that entire exposure, they’ll show up at a normal tone; if they stay in place for 1/2 the exposure, they’ll be half as dark; 1/4 the time, 1/4 the tone. Over the course of that 6 minute exposure, it’s likely that they’ll stay in one place for no more than 30 seconds – that’s 1/12 the time – not enough time to make a meaningful registration on the film. This is exactly what happened in my West Side Market photo – the market was packed full of people, but a 6 or 7 minute exposure erased almost all of them!

[singlepic id=27 w=600]West Side Market, ©Kier Selinsky[/singlepic]

I hope this gets some of those hard-to-ask questions out of the way so that you can start to explore pinhole photography! If you have other questions, you’re surely not the only one – put them in the comments below and I’ll answer ASAP. Cheers!